Earthquakes in Christchurch are not unusual events, we’ve been beset with them since European settlement began – and no doubt long before.

What is most disturbing of all is that our European pioneers knew of the danger that stone and brick buildings posed in earthquakes. Charlotte Godley, who preferred the permanency of stone to timber buildings, wrote that in planning the Christ Church Cathedral, “some of the Committee, however, incline to a wooden frame for the Church, filled in with bricks, which would be much safer in case of earthquakes”.

However, as the city grew and buildings were put up in close proximity, fires became more common events. When alight, the old timber buildings could take out whole city blocks, so replacing them with brick became a priority.

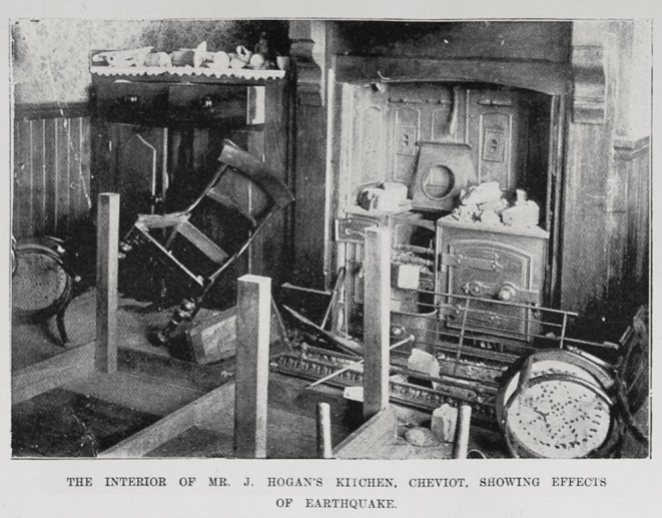

Cheviot, 1901 – a Town Devastated

On November 16th, 1901 a large earthquake, centred in the small town of Cheviot, caused widespread alarm and damage throughout Canterbury. The town of Cheviot was in a state of collapse; brick buildings fell, every chimney was said to have collapsed, windows were shattered. So fierce was the shaking that the body of one Doctor Williamson, who had died a few days earlier, was reported to have been thrown out of his coffin! But saddest of all was the death of little Margaret Johnson, a baby of some 2-4 months old who was inside the family’s small sod house, with an iron roof, which collapsed on the first shock.

The first and terrific shock occurred at 7.45 on Saturday morning.

The town clock stopped.

All brick buildings were levelled, their foundations coming out on top.

In McTaggart’s butcher shop, bricks and meat were all mixed up. The proprietor escaped, but was severely hurt by falling bricks.

Mrs Johnson, of Ben Lomond, had a child killed by falling matter.

Wooden houses were torn from concrete basements, and roofs partly lifted.

Sensation prevailed all day; it was like being on a floating bridge on a rough day. One two storey house was broken in twain at the second floor.

At Parnassus, 12 miles from McKenzie, even worse havoc was wrought, such as the South Island never before saw.

Many people were thrown down, including Mr Robertson, the auctioneer.

Cattle and horses tumbled over, dogs hid their faces and lay down. Horses were nearly mad from fear. Over a hundred shocks were felt, but no damage was caused except by the first shock.

Everybody breakfasted in the open, ladies crying all the time.

The damage in this little township totals about five thousand pounds.

The damage in the entire Cheviot settlement may be safely estimated at £30 per settler, and the loss of some will go into hundreds. The two churches escaped externally anyhow. [2]

In Christchurch, the spire of the Christ Church Cathedral was damaged for a second time, having already sustained earthquake damage in 1888. The model Normal School, built on peaty ground on a corner of Cranmer Square, sustained several cracks on the outside walls. It was reported that if it wasn’t for the buttresses, the whole northern wall would have fallen down. [3]

Earthquake Experiences – a Grocer, a Portly Lady and a Couple of Cats

A greengrocer just happened to be calling when the shock occurred at the house of a rather portly lady, who herself answered the vegetableman’s knock. At the first rumble the lady promptly fainted, and the vegetableman, unequal to the task of holding her up, was borne down by her superior weight, and before he knew what had really happened he was sent sprawling with the contents of his basket liberally and dispassionately distributed over the lady and himself.

At Lyttelton, the Post Office clock bell started ringing, and articles hanging in shop windows were set swinging. In brick buildings the shock was most felt, but beyond the shaking down of a little plaster from ceilings, no mischief happened. Vessels in the harbour were, as one mariner expressed it, “bounced up and down like a ball.”

The shock caused a wave of six to nine inches in the Kaiapoi River from the north bank to the south.

The experience of Mr C. H. Smith, a Christchurch storekeeper, was somewhat startling. He was behind the counter working when the shock came. On the top shelf behind him were about ten dozen pint bottles filled with machine oil, and these began to fall around his head in quick succession. All he could do was to stand with his hands over his head whilst the bottles rattled down, spilling their contents over the goods on the shelves beneath and the goods on the counter. Mr Smith’ luckily escaped any hurt, but the floor was practically flooded with oil, and the same obtrusive liquid made its presence seen everywhere he looked. He estimates the damage done in these few minutes at between £25 and £30.

A servant girl at one of the boarding-houses in the city would have done better to remain inside than to have rushed outside, because when she got out of the door a shower of bricks from above fell about her head. She had a narrow escape. [4]

A gentleman who takes a scientific interest in seismology states that the earth tremor in Christchurch lasted for about an hour, commencing at fourteen minutes to eight. The motion commenced with a steady east to west motion, and then after a few seconds’ cessation recommenced from north to south.

The large concrete tank at the Christchurch railway station was violently agitated, and for ten minutes after the main shock the water splashed over the sides in a two-inch stream.

A little child was standing in front of a fireplace on which there was a large pot of hot water, and its father just arrived in time to save the child from being scalded by the hot water which was splashing out of the pot.

A young lady at Linwood had a somewhat singular experience. She went out before breakfast for a bicycle ride, and when the shock came was gathering buttercups on the bank of the river. All at once she felt very giddy, as if the earth was rocking under her feet as indeed it was and came to the conclusion that she must be feeling faint for the want of breakfast. In some alarm she mounted her bicycle and rode home as quickly as possible, and, of course, the alarming symptoms had passed off before she reached home, and there learned the true cause of her discomfort.

A cyclist who was riding to work when the earthquake occurred got off under the impression that something had happened to his machine and was then thrown to the ground,, bicycle and all.

In moving some timber from a stack the earthquake jammed an up-country workman so that he was temporarily disabled.

Under a large bluegum tree near Leithfield a farmer on Saturday morning picked up from sixty to eighty young birds which had been thrown out of the nests by the shaking of the earthquake. A couple of cats which came on the scene were enjoying the windfall. [5]

‘is it wise to build in brick and stone in New Zealand’

The late disastrous shocks, in North Canterbury have rudely awakened people to the knowledge that there is a very real danger lurking under their feet, and that at any moment the earth may begin to heave and shake so violently as to destroy even the most substantially-built edifices; indeed, the more substantially they are constructed, the greater danger of their destruction. Had the Cheviot disturbances occured as severely in any of the chief centres of population the result would have been appalling, as the destruction of property and injury to life and limb would have been proportionately greater. It therefore comes to this: is it wise to build in brick and stone in New Zealand. Under ordinary circumstances we do not think it is, but we have the example of other places affected by earthquakes to go by, and they have proved that, despite such occurrences, it is possible to erect high brick and stone buildings in such a way as to resist the ordinary force of the earth shakes in that quarter. This is done by erecting a steel skeleton of such buildings, which is then clothed with brick, stone, or cement, bonded with hoop-iron. Such a structure is found to withstand earth shakes that would tumble every brick and stone building in New Zealand into the street, and cause no end of fatalities and injuries to those in them or passing by them at the time. [6]

Images taken from the supplement to the Auckland Weekly News, 05 December 1901. Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries.

To understand the almost panic stricken state of Cheviot it is necessary to have experienced the earth tremors and to witness the effects of them. It is easy from a safe distance to regard the consternation of the inhabitants as excessive, seeing the loss of life has been insignificant, but when you feel your house shaken atop of you as a terrier shakes a rat, and the solid earth rocked and riven, you are one of a million if you preserve all your wits about you. We confess to having made perhaps too little of the effects of the earthquake in Cheviot till we saw the pictures in this week’s “Graphic,” which depict as no words can the actual state of affairs in the township and district. The picturesque reporter may exaggerate, but the camera is the soul of truth. [7]

Sources:

- Image: Alexander Turnbull Library ID: 1/2-022298-F.

- A Special Account, Auckland Star, Volume XXXII, Issue 265, 18 November 1901, Page 5.

- Colonist, Volume XLV, Issue 10260, 18 November 1901, Page 2.

- Christchurch Press.

- “Damage to Christchurch Cathedral. Incidents in and around the City”. Wanganui Herald, Volume XXXV, Issue 10500, 22 November 1901, Page 2.

- Earthquakes Wanganui Herald, Volume XXXV, Issue 10499, 21 November 1901, Page 2.

- Auckland Star, Volume XXXII, Issue 274, 28 November 1901, Page 4.