Remedies, Soaps, Perfumes and Photographic Supplies

Read time approx. 30 minutes.

One of Christchurch’s most well known and successful chemist and druggist shops was owned by George Bonnington.

Following in the footsteps of his oldest brother Charles, George left Nelson in 1872 to set up in Christchurch, opening a small chemist shop. Located on the west side of Colombo Street, between Gloucester and Armagh Streets, it was a modest establishment in the former premises of a ‘Fancy Bazaar’ and stationery warehouse. [1]

Alongside the remedies, soaps, perfumes and infant foods for sale in the shop, Bonnington sold the latest photographic materials from London. He also tried his hand at selling fruit wines, which he had brought down from Nelson. The varieties sported such names as ‘The Riwaka‘, ‘The Motueka‘ and ‘The Wakapuaka‘, which he aimed to sell in bulk at low prices to ‘encourage their general use in the Province‘. [2]

Unfortunately for George, gallons of Nelson fruit wine and home made remedies were not enough to ensure immediate success in the Christchurch market. On 13 January, 1875 he declared himself bankrupt, putting his affairs in the hands of two Trustees – one of whom was his brother, Charles. The Christchurch business was put on the market – stock, fixtures and good will – but no sale eventuated. Instead the business was assigned over to Charles and fellow Trustee, merchant J. J. Fletcher, and together they worked to turn the business around.

Advertisements for George’s Irish Moss preparation, a remedy for severe coughs, cold, asthma, influenza and bronchitis which had proved popular in Nelson, were placed regularly in the Star, becoming the cornerstone product for the business. Before the year was out, they had relocated the business to a larger shop on High Street – in the premises previously occupied by W. Strange and Co., not far from the Lichfield Street corner – and advertised for ‘an experienced and steady man‘ to manage the business. The lucrative Nelson business was also placed on the market. [3]

By the end of 1876, ‘Bonnington’s Pectoral Oxymel of Carrageen or Irish Moss’ was being distributed and sold through stores and chemists throughout Canterbury. [4]

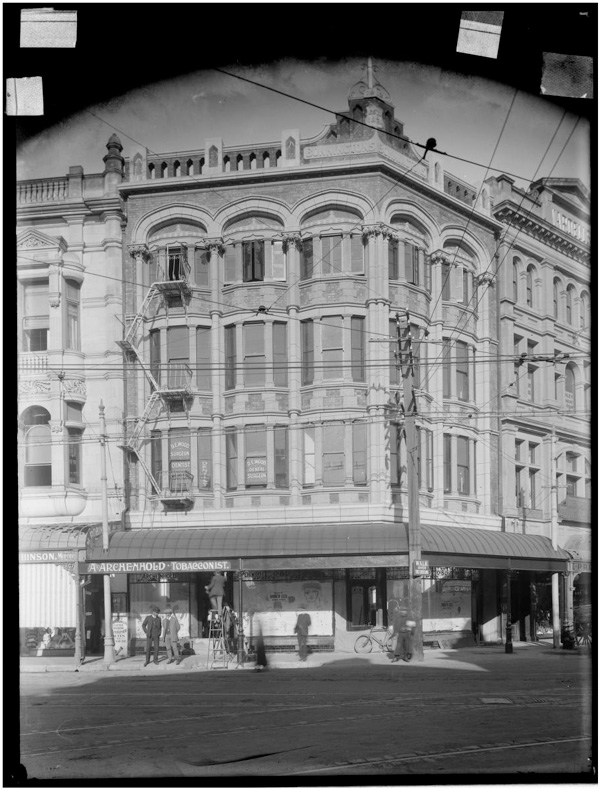

In 1883, Bonnington & Co. relocated to the newly constructed, ‘custom designed’ Bonnington House at 199 High Street. This elegant sandstone Italianate building was the work of Christchurch architect, Thomas Stoddart Lambert. Lambert was also responsible for designing several other important city buildings which included:- the Jewish Synagogue (1881-1895), the United Service Hotel (1885 – 1990), the former Opera House (1883) and Church House on the north-west corner of Cashel and Manchester Streets.

The right hand side of the building was occupied by the very successful drapers, Black, Beattie and Co. Mr. Beattie, the younger of the two partners of this business, was very entrepreneurial and also ran several farms in South Canterbury.

Prior to building Bonnington House, a pair of double storey commercial buildings dating back to the very early days of Christchurch had to be demolished. These very early colonial buildings housed a small post office ‘come’ grocers, while in the other building was a fancy repository called Montague & Co.

Bonnington House had a Lamson pneumatic cashier machine installed – the first in the Southern hemisphere. The shop counters were connected by tubes to a central cashier to whom the customers’ payments would be despatched. The cashier would then return the change and receipts to the shop assistants in cartridges that were driven along overhead pipes by compressed air.

Bonnington imported drugs and sundries, and sold a huge selected stock of toilet requisites and medical appliances of the latest description. The building’s ‘raison d’etre’ was decorated with a large stone carved mortar and pestle which was placed on top of the building’s pediment.

Bonnington’s Irish Moss

Bonnington’s Irish Moss or “Pectoral oxymel of Carrageen” made George Bonnington an extremely wealthy man. An entrepreneur from a young age, he was still living with his family in Richmond near Nelson, when he concocted the clear, dark brown syrupy cough mixture of vinegar and an extract of seaweed, – carrageen – sweetened with honey.

Carrageen, known commonly as ‘Irish Moss‘, had been used as a thickening agent in jellies, blancmanges and broths for hundreds of years. It’s medicinal qualities were well recognised; mixed with milk, sugar and spices, it could be made into a nutritious and easily digested decoction for invalids suffering from consumption, coughs, asthma or dysentery. [7]

American Physician, Dr. Flodoardo Howard, from Washington City, prepared and sold “Compound Syrup of Carrageen or Irish Moss” in 1836. In Sydney during the early 1850s, Irish Moss was sold as part of a bush medicine chest by chemist and druggist C. M. Penny, around about the time George was studying there, and through W. R. Grundy in Auckland. [8]

Bonnington guaranteed that one dose was an effective cure for any cough. It’s sweet odour and taste was responsible for making it one of the most popular medicines of its day. However, the taste had probably more to do with the secret ingredients – opium and morphine – which provided a pleasant after taste and effect!

In about 1891, Bonnington & Co introduced their Irish Moss preparation to the Australian market, opening a factory in Harris Street, Sydney. It was advertised as containing nothing injurious and ‘there is not the least danger in giving it to children‘. Yet in 1907, a Victorian grocer was fined in the District Court for selling Bonnington’s Carrageen Irish Moss, which contained morphia – contrary to the Pure Food Act. The bottles were quickly withdrawn from the market and a fresh batch prepared which didn’t contain any opium derivative. [9]

Bonnington’s trademark line “start that sip, sip, sip of Bonnington’s Irish Moss” was used for years to promote the continued consumption of the product, and it is still being manufactured today… in Australia!

George Bonnington’s Early Years

George Bonnington was just twelve years old when he arrived in Wellington, New Zealand with his mother, six brothers and two sisters in 1849. They were travelling to join their father Joseph, who had arrived in New Zealand only four months earlier – originally bound for Otago. The Bonningtons sailed across to the settlement of Richmond, south of Nelson, where fertile land ideal for farming was being offered by the Nelson Company. They built a cob cottage to house their large family on land they had acquired in Richmond in 1853. [10]

There wasn’t much call for boot and shoemakers in colonial New Zealand, so Joseph Bonnington left behind his trade in the family’s home village of Chesterfield, Derbyshire, and travelled to New Zealand as an agricultural labourer. However it was only a matter of a year or two before he resumed the trade he had left behind, in Bridge Street, Nelson, whilst his offspring continued to farm land near where they had settled in Richmond. [11]

The oldest of the Bonnington boys, Charles Joseph, who as 20 when he came to NZ, was a talented musician and gave lessons in music and dancing. From an early age he had played the violin and piano, and composed dance music – his “Emmeline Polkas” were published at age 16. Charles became the first professor of Music in Nelson, and established the Nelson Amateur Musical Society, in which brothers Henry and George were pianists.

After moving to Lyttelton, Charles took over the Christchurch book and stationery business of a Mr Whincop in 1862, located in the York Buildings on High Street, and introduced a music and musical instruments department. Another move occurred to a large shop, hall and store in Cathedral Square, which he then vacated in 1864, after escaping damage from the fire that decimated three blocks of buildings located opposite in June of the same year. [12]

Music was Charles’ passion, so after about two years located on the corner of Cashel and Colombo Streets, he sold off the stationery and book binding department in early 1866, to concentrate on music and instruments. Not only was Charles a talented musician but also an astute business man, who pioneered hire purchase for pianos. He left Christchurch for Auckland in February 1869 to set up a similar business in Wellesley Street. [13]

In the early days, whilst Charles was establishing an enviable reputation as a gifted and generous musician, George was completing his secondary education at the first Catholic College in Nelson. He then sailed to Sydney to study chemistry. After completing his studies in 1854, he returned to Nelson and opened his first chemist business. Around this time, George concocted his own cough mixture which would become one of the most well known medications in Australasia. [14]

George went into business with established Nelson chemist and druggist, Evan Prichard, who was about ten years his senior. They opened a drug and general store in Trafalgar Street in 1862, and were advertising Pectoral Oxymel of Carrageen as a “valuable remedy for Coughs, Colds, and Influenza. For adults and children of any age…” The preparation was sold in 1, 2, 3 and 5 shilling bottles, and their advertising stated that it had been very extensively used for many years in Australia. [15]

In 1864, George Bonnington ended one partnership and started another. Prichard & Bonnington dissolved their business partnership by mutual consent, with Bonnington carrying on the business in Trafalgar Street (Prichard would return to Nelson in early 1877 to take over this business which by then was known as Bonnington & Co). [16] George also married Isabella Kirk, and son, George Hartley was born in Nelson not long after.

Drama and Tragedy in Settler Life

Life was often difficult for early settler families, and the Bonningtons had more than their share of dramas and tragedies. Theirs had been a large family by today’s standard, but with many Victorian children not surviving beyond infancy, this was not uncommon. Not even the ‘sip, sip, sip’ of Bonnington’s Irish Moss, nor George’s training in medicines, could prevent disease from taking the lives of Bonnington family members.

Just over a month in late 1879, George and Isabella buried three children under the age of four and a half. Louis aged four, was buried 21 November 1879; Lilian aged two – just nine days later; and baby Hilda, only eight months old, was buried on 30 December 1879 – all at Woolston’s Rutherford Street Cemetery. After moving from Christchurch to Auckland, Charles Bonnington and his wife lost their six year old daughter, Lilly and three month old son, George Joseph on subsequent days in May 1872. George’s sister, Mary Ellen Bonnington, a governess living in St Albans, died at age 27, on May 11th, 1877. And as you will read further down, their then remaining sister, Emma, would also meet with an untimely death in tragic circumstances. [17]

George’s father, Joseph, suffered for a number of years, prior to his death in 1870, from what we might now attribute to Dementia or Alzheimers Disease, but which his family called insanity. Henry Bonnington, the third son, described his father as having withdrawn from society, not being able to remember people and incapable of transacting his own business. According to Henry, one of their siblings had also spent a number of years as an inmate in the Wellington Asylum.

Henry’s own daughter, Fanny, was a young woman of sixteen, working as a servant in Wairau for Mr Henry Dodson, who was a member of the House of Representatives, when she was brought before the Blenheim court on a charge of infanticide. After working for Dodson for just six months, all the while concealing a pregnancy, she gave birth to a child on 3rd July 1884. The next day, the body of the baby was found in the water closet (toilet), having died from bleeding from the umbilical cord. Her Council argued that she was insane, pointing to the apparent insanity of her grandfather and uncle. According to Fanny’s parents, she had suffered from whooping cough five years previous and had been behaving oddly afterwards, with episodes of sleepwalking, and an inability to stand excitement. [18]

Thankfully Fanny’s ‘insanity’ was short lived. After the jury returned their verdict of insanity, she was packed off to Mount View Asylum in Wellington for what turned out to be a relatively short ‘sentence’. She spent several months there, kept apart from the other patients, working as a servant in the kitchen. Despite being declared ‘quite silly‘, she well enough to be released back into her family’s care at the end of January 1885. [19]

At home in Christchurch

George, Isabella and their children lived in a large house called ‘Hazlewood’ on Ferry Road in Woolston. The ten roomed wooden house was situated on 3 1/2 acres of beautiful grounds, with stables and outbuildings. [20.] The family kept emus as pets and these large animals proved a popular drawcard with all the neighbourhood. They were also eagerly enjoyed by passengers on the upper deck of the Sumner trams who would watch out for them as they passed their house.

George, like his brothers, was keen on music and made sure all his children played an instrument. They created a family orchestra, which practised on the top floor of Bonnington House. His eldest son was instrumental in founding the Woolston Brass Band and Miss Bella Bonnington was well recognised as a soprano, in much demand among the province’s musical circles. After completing her education at Girls’ High, she travelled around the world in 1898, accompanied by her father, enjoying the afternoon concerts in London and the ‘perpetual brightness and gaiety of Paris’. She returned to Christchurch before the year was out, reportedly her voice having ‘improved greatly since her trip Home‘. [21]

For six years George was a City Councillor, representing the South-East Ward. He was also a founding member of the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand which had its first conference for members from all parts of the Colony in Wellington. He became secretary and treasurer of the society until the body was closed and a Pharmacy Board, of which he became a member, was appointed. He assisted in the conduct of examinations held under the authority of the Pharmacy Board and attended conferences of the Pharmaceutical bodies in Melbourne. In musical circles he was also very popular, and was one of the founders of the Christchurch Orchestral Society. He also took considerable interest in church affairs, municipal politics and bowling! [22]

At the age of 64 years, George Bonnington died on December 18th, 1901 and was buried in Linwood Cemetery. He left his widow, Isabella, seven sons and two daughters. Their son, Leonard, followed in his father’s footsteps – professionally and musically – and was made managing director of the entire business.

New High Street premises

Bonnington & Co continued to grow. Leonard built Bonnington’s four storey building at the corner of High and Cashel Streets, next to Wardells, in 1911[endnote 222 High Street, occupied by the boutique fashion store Jean Jones in the 1990s and 2000s, located opposite Westpac] and they remained in business on the ground floor until 1973. The department store magnate, William Strange purchased the elegant white Bonnington House so he could expand his adjacent department store. However Strange and Co. went into liquidation and closed down in 1929, and J. R. McKenzie acquired the building. In later years, the building became dilapidated and its decorative cornice and pediment were removed.

After Leonard retired, his brother, Louis (b. 1875) and then Cecil (1886 – 1965) took over the business in succession. Since 1959, a reproduction of Bonnington’s Chemist and Druggist can be viewed in the Victorian Street at the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch.

About 1988, Bonnington House caught fire and the upper two floors were destroyed until restoration by the KPI Rothschild Property Group in 2007.

Death on the doorstep

Due to their central city location, Bonnington’s Chemists were often presented with serious cases which required their assistance.

About eight o’clock, on 27th February 1885, Tomaso Robelli, an Italian fisherman was walking towards Bonnington’s on High Street when he was seen to stagger and a jet of blood gushed out from his mouth. He tried to get inside the chemist but collapsed before reaching the door. Mr Dodds, the dispenser and Mr Buchanan rushed to his aid and carried him in. They presumed he had broken a blood vessel (aneurism) so were sure that nothing more could be done for the man. He died within five minutes later and Constable Hayes, who had arrived shortly after they brought him, sent for the police trap to take his body to the morgue at the Hospital.

Robelli was only forty years old but had been suffering bad health and had an empty medicine bottle in his jacket which they presumed he was taking to Bonnington’s to have filled. [24]

Mystery women’s last breath in Bonnington’s

One summer’s evening in January 1904, a short and rather stout lady of about fifty six, entered the chemist. Laden with bags and clutching a medicine bottle, she had hoped to have it filled with a prescription to treat her symptoms. Suddenly, before being served, the woman collapsed to the floor. Bonnington and his staff went to her assistance, but found that she was dead. Alone and with no identification on her body, the police could only take a physical description of her in the hope that her family would eventually report her missing.

Her grey hair had been tied back at the base of her neck in a bun and she wore a long black lustre skirt, checked bodice and a sailors hat with a white band. It was thought she may have attended the Christchurch Gas works picnic the day before, as similar toys in her bags had been given away as prizes. Eventually her worried family contacted the police and her identity was solved. She was Lucy Jane Hicks, who had resided in Gladstone Terrace. Her post mortem carried out by Dr. Symes, concluded that Mrs Hicks had died of a heart condition. Her heart, lungs and kidneys were diseased and, as a slave to past fashions, her chest was deformed through tight-lacing. [25]

Hydrochloric Acid in a beer bottle

About the time this photograph was taken, Bonnington’s Chemist became embroiled in a case of a poisoned woman. The victim’s husband, Mr. John Lamb, was claiming two hundred pounds damages against Bonnington’s in the District Court, on 6th March 1885.

It appears that Bonnington’s ‘servant’ had sold three pence worth of hydrochloric acid to a plumber called Frederick Ward who was working for Mr. Lamb. The poison was poured into an unlabelled herbal beer bottle which Ward had brought with him. Ward stated in court that,

“The shopman who served him did not put on any label, nor make any remark as to the contents of the bottle which was not wrapped up in anything. He had been in the habit of buying hydrochloric acid, and had never before bought it without a label with the words, “Spirit of Salt: Poison” being placed on the bottle.”

After his purchase, Ward went to Mr. Lamb’s house to fix the pipes. He only used a quarter of the poison before carelessly leaving the bottle sitting on a barrel outside in the backyard. Later, Mrs Parker’s sister, Isabella, who was looking after her ill sister, saw the bottle and thinking it contained beer, put it away in the kitchen cupboard. Later, after feeling thirsty, Isabella got it out and drank from it. The acid burnt her mouth, oesophagus and stomach. She grabbed a jug of milk and swallowed as much as she could to reduce the poison’s effect but it had already seriously burnt the skin in her mouth and tongue.

“She then became senseless, and did not recover consciousness till Dr. Deamer was attending her.”

For the next month, she remained very ill and had not recovered by the time of the court case. His Honour Justice Ward, concluded that, although Isabella had drunk pure hydrochloric acid, its ability to be diluted omitted it from the schedule of the Poison Act, so therefore it was not the legal responsibility of the chemist to have labelled the beer bottle. Blame was squarely laid at Ward, who carelessly left the bottle for the accident to occur. [27]

The next evening, the editor of the Star expectorated,

“It seems an uncommonly hard case. From causes that were preventable, that ought not to have existed, a woman nearly lost her life; whilst her husband had to witness the agony of the one nearest and dearest to him, and, seeking in vain redress, has to bear the expenses of medical and legal advice. Yet there can be no doubt that His Honor Judge Ward was perfectly right in his conclusion… there are numbers of preparations not mentioned in the Poisons Act which might be fatally misapplied, and if it were incumbent upon a chemist to instruct purchasers as to the possibilities connected with any and every substance, the rule must hold good for all tradespeople…it is perfectly clear from the report that in assuming the chemist’s assistant to have been morally negligent there is a contributory negligence on the part of the purchaser. We may assume the purchaser knows as everybody knows, that on one occasion hydrochloric acid was fatally used in Christchurch.”

Spectacular window display goes up in flames

Bonnington’s run with his employees seemed doomed. One ‘servant’ managed to set the window display alight after dropping a taper onto inflammable stock on September 15th, 1884. The Star reported:

“Great excitement was caused in High Street on Saturday night, through some of the goods in Mr Bonnington’s chemist’s shop window taking fire. One of the assistants was lighting the gas lamps in the window by means of a taper a the end of a rod, when the burning taper fell on some cotton wool. In trying to reach the taper, the assistant over-turned a bottle of scent, there being at the time a special show of scents in the window, and the volatile spirit at once burst into flames. For a moment or two there appeared to be imminent danger of a serious fire, but the promptitude of a passer-by quickly extinguished the flames by means of a mat damped in the water channel.

Lucky for Bonnington, the fire was extinguished quickly and the damage was minor – “…his loss at about one hundred pounds”. On the alarm being given, the fire brigade headed off in the wrong direction. The wrong number was recorded causing them to head off to the north-east ward of the city.

Struck by a frightened horse

On a winter’s morning in 1885, the limp body of an injured and bleeding young woman was rushed into Bonnington’s. It appears she was run down by a runaway horse.

The ‘Express’ belonging to Messrs. B. Walters and Co., on Victoria Street had been standing on Manchester Street south, when it bolted after being frightened by another horse and cart going by. Unable to stop the horse, it took off up Manchester Street towards High Street where at the junction of these streets, a young woman called Miss Humphreys was crossing in front of some shops.

Seeing the horse careering towards her, she tried to get out of its way, but the shaft of the express struck her and knocked her under the wagon’s wheel which ran diagonally across her body. Bonnington rang the police and due to her life threatening injuries, they immediately ordered a cab to get her to hospital.

Meanwhile, the horse ran down Hereford Street. The wagon’s axle broke and one of the wheels flew off. A man named Stephen South dashed out and grabbed the horse’s head, and although he was hit by the shaft, managed to hold the animal, which came to a halt outside the front of the Shades. The Star reported on Miss Humphrey’s:

“From enquiries made at the hospital, it was ascertained that the sufferer had partially regained consciousness but was unable to give coherent answers to any questions. The extent of her injuries cannot at present be discovered, but it is feared they are serious.” [28]

It was not uncommon to see runaway horses bolting down High Street. Only a few years previous, on October 18th 1881, at about half past three in the afternoon, a horse attached to a Hansom cab belonging to Mr. James Lamb, bolted from the stand in front of the City Hotel, ran down High Street, as far as Mr. Bonnington’s chemist’s shop, where it came into collision with a spring cart owned by Mr. Herbert Bonnington, George’s brother, who was a grocer in Sydenham. Both vehicles were overturned and the cart was damaged to the value of four pounds. The cab was slightly injured and a verandah post of the shop was broken.

One year on from Miss Humphrey’s accident, in February 1886, Mrs Emma Sharp, George’s’ sister, was out driving her carriage in Nelson when her horse took fright and bolted. She succeeded in turning one corner safely, but in going down Bridge street, the carriage struck against a horse post, and she was thrown into the centre of the street, only surviving a few minutes. [29]

Breach of a marriage promise

The dramas Bonnington’s was involved in were not always medicinal in nature. Almost a decade later, in 1893, another employee, chemist Richard Sainsbury, brought disrepute to the establishment when he faced damages of five hundred pounds for breaching a promise of marriage.

Five years previous, when Sainsbury was an apprentice at Bonnington’s, he had asked Miss Gertrude Grace Winstone to marry him. Her father George, a tailor and member of the fire brigade – a sensible man who was concerned for his daughter’s well being – agreed to the union providing that while Sainsbury lodged at the chemists, earning just one pound a week and had an examination to pass,

“the affair should be postponed to allow the defendant to see more of the young lady, and secure a position in life… the young man had become almost a member of the family, being very intimate with the girl.”

However in 1891, Sainsbury’s father, who lived in Capetown, South Africa, asked his son to return home. Sainsbury left under the arrangement that his fiancee would follow him in a couple of years. While he was gone, Grace found employment to save money and supplement her fiance’s income. Sainsbury wrote her letters “expressive of the most profound love.. and it could be proved that his prospects were sufficiently good to warrant marriage.”

Sainsbury returned to Christchurch in February 1893, and resumed work at Bonningtons. Now earning two pounds per week and lodging above the shop, he planned to find a business for himself. However the time apart had also caused a break in Sainsbury’s feelings for Grace, and he began to form attachments to other girls.

“He invented numerous excuses to keep out of her way… He had then formed an intimacy with another girl, and and had taken her to the theatre three times. On being remonstrated with by the plaintiff, he had in the most cold-blooded way told her that his feelings had changed and that he cared for her no longer. He had after this totally neglected her and made her miserable. He had told her that while in Capetown he had fallen desperately in love with someone else. She had never broken off the engagement, she had always entreated him to go to her and explain his actions.”

Letters were read out showing Sainsbury had,

“grossly abused the confidence reposed in him, as being engaged to the young lady, and this the jury should take into consideration when awarding damages.”

The jury awarded a hefty fifty pounds in damages. [30] Whilst Richard disappeared into obscurity, Gertrude didn’t remain ‘on the shelf’ for long. In 1896 she married local bootmaker, Samuel Kennedy, and three children subsequently arrived in quick succession.

Sale of laudanum ends in suicide

George Bonnington was once caught up in a suicide which saw him and William Townend, another city chemist being taken to court on 13th December 1880, facing charges of:

“being registered under the Sale of Poisons Act, he did sell poison, to wit, one ounce of laudanum, and did then and there fail to make an entry in a book kept for that purpose, stating the date of the sale, the name and address of the purchaser, the name and quantity of the article sold, and the purpose for which it was stated to be required by the purchaser and bearing the signature of the purchase.”

George Bonnington admitted the offense. Police Sergeant Morice stated the poison was sold to a man who was afterwards found dead. The man, Charles Hurrell, was clerk of the Resident Magistrate’s Court in Ashburton, but had lately resigned under the belief that there were people out to get rid of him. His wife and son had recently left him and gone to live in Auckland, and he suffered terribly from neuralgia – a sharp, shocking pain that follows the path of a nerve. The only way Hurrell could get any rest at night was to dose himself heavily with laudanum. After resigning his job, he had travelled to Christchurchand booked into Coker’s Hotel. He was found by a friend there, in his room, dead, with an empty bottle of laudanum on the side table, and a full one in his coat pocket.

Bonnington said it had not been the general custom to register every purchase as the man had asked for laudanum in a very straight forward manner, and a person accompanying the purchaser was known to accused. This being a first offense, Bonnington escaped with a fine of 20 shillings plus court costs. [31]

Poisoning and charge of manslaughter, Bonnington supplied an antidote

On 13th March 1904, at the Magistrate’s Court, the Chemist Charles Mytton Brooke of Ferry Road and his apprentice and son, Henry Kaiapoi Brooke, appeared on a charge of committing manslaughter on February 17th, at Sydenham. Due to their negligence, they accidentally mixed strychnine into Amy Sarah Dewey’s medicine, and caused her death.

Amy had lived with her sister, Mary and husband, Benjamin Lowry of Bamford Street, Linwood up until her death. She had “been deformed and delicate in health most of her life”. On Saturday, February 13th, Mary took her sister to Dr. Geoffrey Sherbourne Clayton after she had ‘tightness of breath’ and ‘neuralgic pains in her head’. Clayton wrote a prescription which they took to Brooke’s Chemists, and waited while he made up the prescription. On returning home, Mary gave her sister a dose of the medicine before she went to sleep at ten o’clock. All night Amy experienced a prickly sensation and when she awoke next morning, found she could not walk.

Mary gave her another small dose on Sunday afternoon, at about 2 o’clock, which seemed to give her sister an aching sensation. Despite her reaction to the ‘medicine’, on Monday morning, she was given yet another dose of the medicine – the last dose. Muscular spasms, lasting ten minutes, followed after taking the medicine. Amy took a walk around the garden but soon her arms were stiffening, her back becoming more bent. She lay in a rocking chair, but her face was becoming tinged with a blue colour and feeling very anxious for her deteriorating state, Mary administered some whiskey and went for Dr. Clayton. He arrived at 1.30pm and after his visit, Amy went to bed.

In the company of Mary, the doctor went to Mr Brooke’s chemist shop and asked to see Brooke senior. He was not there so they spoke to his son.

Later, in consultation with Brooke senior, the doctor informed him that that the medicine contained strychnine and asked him how this might have occurred. Brooke explained that his son had made up some poison for rats or mice for a neighbour named Dixon. The Brookes were well known for their pest control preparations, including Brooke’s ‘Perfect‘ sheep dip. He had ground up some strychnine in water and put the mortar away uncleaned. He must have then used the same mortar in making up Amy’s prescription.

The doctor went to Bonningtons to get an antidote, and took it to Amy. She was in a shaky, tremulous condition and her breathing was worse. He gave her a dose of the antidote and instructed Mrs Lowry to repeat the dose every four hours should any muscular spasms appear. On Tuesday, he found her breathing was irregular and distinctly worse, although her mind was quite clear.

She was examined by Dr Clayton and Anderson about six o’clock on Tuesday evening. Her condition had declined since that morning. They concluded she was suffering from pneumonia caused by the strychnine congesting the lungs. They saw her again on Wednesday and were struck by the very decided tetanic spasm of the left arm. She gradually became worse and died about four o’clock that afternoon. It was concluded that the quantity of strychnine found in the analysis would be a dangerous dose to any person in the condition of the deceased.

This, however, was not the first, nor the last, poisoning case that chemists Bonnington, Townsend and Brooke found themselves embroiled in. As all these stories reveal, the life of a chemist in early Christchurch was anything but dull. [31]

Sources:

- Star, Issue 1674, 8 July 1873, Page 1.

- Star, Issue 1698, 6 August 1873, Page 1 and Star, Issue 1881, 13 March 1874, Page 1.

- Volume XXIII, Issue 2948, 1 February 1875, Page 4. Press, Volume XXIII, Issue 2969, 25 February 1875, Page 1. Press, Volume XXIII, Issue 3031, 10 May 1875, Page 4. Press, Volume XXIII, Issue 3053, 4 June 1875, Page 1. Press, Volume XXIII, Issue 3073, 28 June 1875, Page 2. Press, Volume XXIV, Issue 3124, 27 August 1875, Page 1. Evening Post, Volume XII, Issue 128, 27 November 1875, Page 3.

- Star, Issue 2652, 26 September 1876, Page 4.

- Image: Christchurch City Libraries File Reference CCL PhotoCD 5, IMG0056. Source: Henry Thomson lantern slides.

- Source: New Zealand Times (Newspaper. 1874-1927); New Zealand Mail (Newspaper. 1870-1907); F W Niven & Company. Image: National Library of New Zealand Ref: D-002-005

- “Carrrageen, or Irish Moss” The Daily Pittsburgh Gazette – Nov 25, 1835

- Jun, 26, 1836 – American & Commercial Daily Advertiser.

Advertising. (1850, April 25). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), p. 1 Supplement: Supplement to Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 22, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12917421

New Zealander, Volume 6, Issue 433, 8 June 1850, Page 1. - 1901, August 24, Western Mail, Perth, p. 56.

“PATENT MEDICINES. A VICTORIAN PROSECUTION. Melbourne, December 3.” The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA) Friday 6 December 1907 p 8. - Joseph Bonnington senior was believed to have sailed on the ‘Mary’ from London arriving in Wellington on 14th March 1849 via New Plymouth & Nelson, then on to Otago 11th April 1849. Source: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ourstuff/Mary.htm

Harriet along with children, Charles, age 20; Henry, 16; Emma, 14; George, 12; Joseph, 11; Herbert, 8; Frederick, 5; Christopher, 4; and Mary Ellen, 2; departed London on board the ‘Mariner’ on 11th February 1849, arrived Port Chalmers 5th June 1849 and Wellington 12th July 1849. Extracted from White Wings vol 2 by Sir Henry Brett. Source: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ourstuff/Mariner.htm

“Bonnington Cob Cottage”, Historic Places Trust Register, http://www.historic.org.nz/TheRegister/RegisterSearch/RegisterResults.aspx?RID=1675 - Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume IX, 15 February 1851, Page 4.

- Press, Volume III, Issue 63, 26 July 1862, Page 8

Lyttelton Times, Volume XXII, Issue 1330, 13 December 1864, Page 7 - Lyttelton Times, Volume XXV, Issue 1589, 16 January 1866, Page 1.

Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume XI, Issue 571, 12 February 1853, Page 203. “In Memoriam” Nelson Evening Mail, Volume XVIII, Issue 283, 1 December 1883, Page 3.

Nelson Evening Mail, Volume IV, Issue 31, 8 February 1869, Page 2; ‘The New Music Rooms Wellesley Street” Daily Southern Cross, Volume XXV, Issue 3713, 12 June 1869, Page 5. - The Canterbury Times, page 43, December 25, 1901.

- Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume XXI, Issue 43, 21 May 1862, Page 2 and Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume XXI, Issue 46, 31 May 1862, Page 2.

- Colonist, Volume VIII, Issue 746, 20 December 1864, Page 2. Nelson Evening Mail, Volume XII, Issue 21, 24 January 1877, Page 4.

- Christchurch Cemetery records and Church Index Cards located at Christchurch Library

Daily Southern Cross, Volume XXVIII, Issue 4585, 4 May 1872, Page 2.

Nelson Evening Mail, Volume XII, Issue 111, 12 May 1877, Page 2. - Marlborough Express, Volume XX, Issue 338, 21 October 1884, Page 2.

- Marlborough Express, Volume XX, Issue 363, 21 November 1884, Page 3. Fanny married a local farmer, David Herd, in 1899 and the couple had at least four children.

- Star, Issue 8058, 9 July 1904, Page 6.

- Press, Volume LV, Issue 10123, 24 August 1898, Page 5 and Press, Volume LV, Issue 10172, 20 October 1898, Page 5.

- Canterbury Times, Page 36, Jan. 1, 1902. “The late George Bonnington”.

- Source: Photograph taken by the Steffano Webb Photographic Studio, Christchurch. Image: Alexander Turnbull Library File Reference ID: 1/1-003977-G.

- Star, Issue 5247, 28 February 1885, Page 3.

- Past Papers, Press, Volume LXI, Issue 11806, 2 February 1904, Page 6. Also: Star , Issue 7923, 30 January 1904, Page 5.

- Messrs Bradley, photographers. Image: Christchurch City Libraries File Reference PhotoCD 13, IMG0086.

- Past Papers, March 6th, 1885 page 3.

- Past Papers, The Star, 12th June 1883.

- Marlborough Express, Volume XXII, Issue 41, 17 February 1886, Page 2.

- Past Papers, The Star, 23rd November, 1893. Also Press, Volume L, Issue 8651, 28 November 1893, Page 6.

- Past Paper, The Star, December 13th, 1880. Also: ‘Inquest” Press, Volume XXXIV, Issue 4788, 7 December 1880, Page 3.

- Mysterious Death, Star , Issue 7940, 19 February 1904, Page 4

Charge of Manslaughter, Star , Issue 7960, 14 March 1904, Page 3Another poisoning involving Brooke: The Late Poisoning Case, Star , Issue 6596, 21 September 1899, Page 4Townend and Bonnington caught up in court again: This Day, Star , Issue 5359, 11 July 1885, Page 3The Conway Case: Conclusion of the Inquest, Star , Issue 7060, 28 March 1901, Page 1 - Image: Hocken Archives and Manuscripts – UN-023/147 One of Christchurch’s most well known and successful chemist and druggist shops was owned by George Bonnington.

2 Comments Add yours